02 Feb 2023

Levelling Up: Inequality should not be inevitable

It wouldn’t be the most controversial thing to say that the government’s Levelling Up programme has left rather a lot to be desired so far. Funding pots have been inadequate and have not been commensurate with the level of opportunity. The allocation of money has faced heavy criticism on the basis that it is being spent in areas that don’t need it half as much as others; I’ve seen the term ‘pork-barrel spending’ used a few times over the last couple of months to describe the decisions that have been made.

While the Bill continues to progress through Parliament, the debate seems to have shifted to what Levelling Up should be called. The debate should be about designing and implementing a fair, transparent and robust funding mechanism so that we can understand decisions and give the areas left behind some chance of success. If nothing else, the current lack of clarity undermines public confidence in the legitimacy of the Levelling Up mission.

But before I go any further, lets first touch on what Levelling Up really means. Its ambition is to reduce the imbalances between areas and social groups through multiple projects intended to improve transport, communication, education, skills, healthcare, urban regeneration, and more. The Levelling Up White Paper sets out how the government intends to spread opportunity ‘more equally’ across the UK. The term itself was a key slogan of the Conservative Party’s 2019 election campaign under Boris Johnson as Prime Minister but when the Bill was published in May 2022 many felt it was a mismatch of policy proposals that could (and should) have their own legislation – such as the proposals for a reformed planning system. It’s been described by many parliamentarians as a missed opportunity.

The Fund

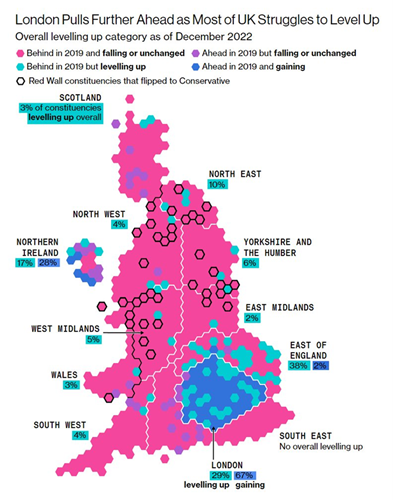

The second round of successful Levelling Up Fund bids were announced last week. £2.1 billion of the £4.8 billion fund was awarded to over 100 projects across the UK. Think-tank IPPR North’s analysis of the data tells us Yorkshire and the Humber received a third less than it did in the first round, and London received more than double. Blackpool is the most deprived authority in England and was unsuccessful across all bids - as was Middlesbrough. Notably, though, Bromsgrove in the West Midlands (Sajid Javid’s constituency) was successful, while Coventry, which is considerably less affluent than Bromsgrove, wasn’t given any money. What stands out the most from this analysis is that the East Midlands received the most - having received more than half of the funding it asked for, and 10 per cent more than the North East, the most deprived region in England. Government claims that it remains committed to the levelling up agenda, but current metrics raise questions.

Source: Bloomberg

The Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Michael Gove MP spoke at last week’s Convention of the North announcing £30 million for Greater Manchester and the West Midlands to improve the quality of social housing. Mr Gove said his department would “shortly begin the process to identify more investment zones in areas in need of levelling up”. But what government seems yet to do is recognise the limits of the top-down approach to Levelling Up: while central government retain the initiative, areas ‘in need’ will continue to be cherry-picked.

The North

The North is too often at the forefront of inequalities in productivity, incomes, housing options, pollution, and educational opportunities, as highlighted in analysis from IPPR North.

The latest data from Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s UK Poverty 2023 report shows that the North East had the highest regional poverty rate in 2018–21 at 26 per cent. Yorkshire and The Humber also have higher than average poverty rates at 24 per cent and 23 per cent respectively. In these areas, higher poverty rates are driven by comparatively lower earnings, with a higher proportion of adults working in lower-paid occupations, and higher rates of economic inactivity and unemployment among working-age adults. People in these regions are disproportionately likely to rent their home and the regions have the highest poverty rates for renters across the UK, with renters typically in poverty before housing costs are factored in.

A new report analysing the impact of the cost of living from the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) Child of the North found an extra 160,000 children were living in poverty in the North compared to the rest of England during the pandemic. These children are among the most vulnerable to rising living costs and are more likely to be living in fuel poverty and food insecurity. Across the North East, Yorkshire and the Humber, child poverty is the highest it has ever been.

I attended the Northern Housing Consortium Summit recently and heard Karbon Homes talk about their new report setting out the real challenges for ‘left behind’ places and how housing associations can take a new approach to tackling them at their root. I was born and raised in Newcastle upon Tyne so I’m familiar with the city; what I wasn’t aware of until recently is the shocking life expectancy disparities between areas, with a 12-year difference between people living in Gosforth and people living in Byker. Byker has a staggering 47.5 per cent of children living in poverty, while 4.9 per cent of children are living in poverty in Gosforth. So, while we recognise regional inequalities, it is vital we address the inequalities within regions too.

On that note, devolution does seem to be shifting in the right direction. Giving power to local authorities allows for flexibility in determining priorities and strategic goals, and last week the North East agreed a historic mayoral devolution deal. The most important part of this initiative is that the cash is being given directly to the regional commissions to spend as they see fit, which differs from Whitehall’s approach to Levelling Up, which requires councils to put forward specific projects for government approval. The echo from Northern leaders is that rather than piecemeal funding, they want a single lump sum given to each devolved area to spend on their priority areas. As we anticipate a general election, both major parties are seeking to embrace greater devolution to address the regional inequalities across the country. Dedication from both parties on this agenda is welcome, and meaningful, robust policies and adequate funding – especially around housing and adult skills – should form the core of the anti-inequality agenda.

Everyone deserves a fair chance; to live in a safe, affordable home and to exercise their full potential in all aspects of life. But as it stands, that chance depends on where in the country you are. For Levelling Up to succeed, it must create strong, resilient, and sustainable places where people can thrive. Reducing regional divides in the country would unlock national growth and produce better outcomes for everybody.

Alexandra is a CIH policy and public affairs officer responsible for monitoring the impact of the Levelling Up agenda and leads on our public affairs and parliamentary engagement work to develop and maintain CIH's influence.