22 Dec 2022

The cost of living crisis and social sector rents

September’s mini-budget gave little extra help to poorer families apart from its pre-announced support for fuel bills, writes John Perry in this edited extract from UK Housing Review Autumn Briefing Paper. And even the benefit uplift announced in the Autumn Statement will leave many households struggling.

Social landlords are debating how best to respond to the cost of living crisis, with many having hardship funds and other mechanisms to assist tenants. A key issue is whether to raise rents in April 2023, and if so by how much. In Scotland, there is now a rent freeze until at least March, with suggestions that it might continue into 2023/24. Northern Ireland has seen a freeze on Housing Executive rents this year although housing associations are so far unaffected. Wales has announced a 6.5 per cent cap on increases.

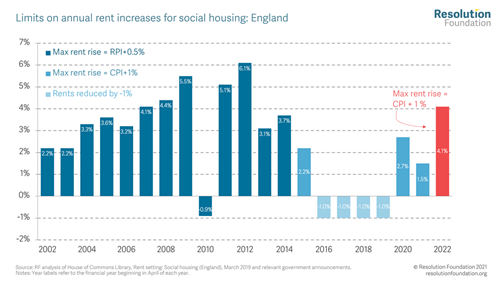

Debate in England focused on the government consultation paper with options to limit rent increases, which have since been capped at seven per cent. The CPI +one per cent limit which applies in 2022/23 replaced a ‘ten-year’ policy set in 2015/16, which subsequently suffered several changes. The current one, in turn, is about to be breached after the November announcement.

Limits on social sector rent increases in England, 2002-2023

Source: Based on a chart by the Resolution Foundation.

While CPI inflation is running at 11 per cent, social landlord cost increases are estimated by Savills at similar or even slightly higher figures, with lower salary costs offset by higher contractor and utility costs. Costs of new borrowing have also doubled in the last year. Social landlords will now need to cap their income at less than inflation but, unlike energy companies, receive no government compensation. Nevertheless, there appears to be consensus that rents simply cannot be raised by CPI + one per cent given the intense cost of living crisis faced by the one-third of tenants whose rents are not covered by benefits, and the sector is relieved that the government-imposed cap is seven per cent rather than an even lower figure.

The effects on sector finances will still be considerable. Compared with an increase that fully covers inflation, Savills estimated the impact of the previously forecast five per cent cap on annual income as up to £500 million for councils and up to £1 billion for associations. Local authorities have tighter margins than housing associations, but in general they welcomed the consultation as it facilitated some rent increases when there might be local political pressures to freeze rents completely. However, one large housing association indicates that even the seven per cent cap means a 21 per cent cut in new build, while three per cent would have ended three-quarters of new development and required pulling out of existing contracts. Longer-term impacts depend on how policy is framed beyond 2023/24.

There is major concern about the effects on investment in the existing stock. While fuel costs escalate, there will be enforced delays to energy-efficiency programmes often aimed at the worst stock. One landlord calculates the difference in heating bills for their worst compared with their best homes at about £2,000 annually. This neatly illustrates the strong case for recycling housing benefit savings that result from a rent cap back into the sector, both to maintain investment in the stock and to sustain the funds used to mitigate tenant hardship.

Supported housing providers are particularly challenged by rent caps because escalating costs potentially make schemes unviable, prejudicing their future. They argue that practically all supported tenants receive benefits anyway, so get no advantage from a rent cap. Fortunately, the government decided not to impose a cap on rent increases in this part of the sector. For shared owners, a voluntary ‘cap’ means that the rents they pay should also increase by no more than seven per cent.

Finally, a huge issue for low-income tenants continues to be restrictions in the benefits system such as the overall benefits cap, inadequate local housing allowances and the ‘bedroom tax’, all of which were set in a different environment. While they are helped if rents are held below inflation, recipients would be helped more by revision or abolition of these restrictions on their benefits. Unfortunately, the government appears to be set on a course which will increase hardship rather than ease it, notwithstanding the welcome uprating of benefits and of the benefits cap. One landlord’s assessment of tenants’ precarious household finances led them to comment that many families with children could be left completely destitute, even if rent rises are now held well below inflation.

John is a policy advisor here at the Chartered Institute of Housing. He edits the UK Housing Review and also advises on a wide range of subjects including planning, local authority finance, plus much more. John is a chartered CIH member.