21 Oct 2024

Safe accommodation for asylum seekers - provide it more effectively and at lower cost

Kate Wareing, Chief Executive of Soha Housing, says with the right investment now and collaboration between the Home Office, the Ministry of Housing and our local authorities, we could save a lot of money in the long run and provide homes where needed most.

The system of accommodation for asylum seekers in the UK is not working. With current numbers of asylum seekers making new claims - 84,425 individuals in 2023 - and delays in processing them, there is simply not enough accommodation available in normal housing stock. As a result, the government has been forced to put large numbers of people in ‘contingency’ accommodation – often hotels – for long periods. There is also a parallel shortage of accommodation for homeless households which has led to increased use of hostels and hotels by local authorities.

From the taxpayer’s perspective, this is cripplingly expensive – the Home Office spends around £8 million per day on hotels while councils spend over £1.7 billion annually on all forms of temporary accommodation (TA). From the perspective of those accommodated in hotel rooms, often for over a year, the experience is extremely difficult and often re-traumatising. From the perspective of local residents, businesses and councils in areas with concentrations of hotels accommodating asylum seekers, the impact on communities and tourism industries can be considerable. And of course, asylum hotels make easy targets for anti-immigration protests, exposing residents to extreme hostility.

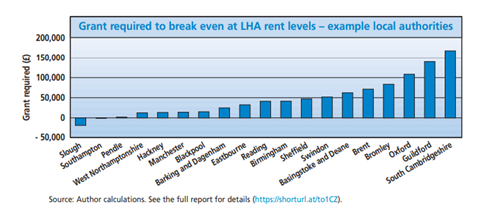

But this could be different. Using available data for every local authority in England we have modelled how much grant would be required to enable a home to be bought on the open market and let at local housing allowance (LHA) levels.

Compared to current spend on hotel accommodation by the Home Office, the cost of providing the capital grant would be recovered in only seven months from the savings in lower, LHA rent costs compared with hotel charges:

- Average cost per person for hotel accommodation is £54,020 per annum.

- In comparison, accommodating three people in a three-bedroom house saves on average £150,395 per annum (the difference between the cost of a hotel and the rent for a three-bed house at average LHA rates).

- Except for a few outliers with very high or negative costs, the grant required to allow remaining costs (running costs plus interest charges) to be covered by LHA varies from zero to £192,000 with an average of £80,000.

- This means that in 91 per cent of local authority areas in England, the grant needed to enable the purchase of homes to be rented at LHA rents would be fully repaid from revenue savings in under one year.

When we initially made these calculations in summer 2023, 48,000 people seeking asylum were staying in hotels. If we had begun purchasing homes then, by now over 16,000 homes could have been procured with the capital grant costs fully recovered from savings on hotel charges, and the cost of accommodating those 48,000 people would have been £2 billion cheaper in the subsequent 12 months.

As the determination of asylum claims has quickened, the number of asylum seekers in hotels has fallen to 36,000 (March 2024). If those 16,000 homes had been purchased in 2023, 12,000 would still be in use in the asylum system (on the assumptions above), leaving 4,000 homes available to meet local homeless families’ needs at a rent equal to the LHA. These could replace dwellings leased at much higher costs by local authorities from private landlords to meet their TA obligations.

Every year that we incur revenue costs on such expensive accommodation is a wasted opportunity to increase the stock of homes available to meet the responsibilities to both asylum seekers and to homeless households. A national supply of TA across all local authority areas would reduce costs to the state, provide better quality accommodation to people through a time of trauma, and add to the supply of affordable rented accommodation.

There are two key prerequisites: willingness to make capital outlays before savings are achieved, and willingness on the part of the Home Office and Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government to cooperate to put such a scheme in place.

This is an abridged version of Kate’s article for the 2024 UK Housing Review Autumn Briefing Paper, which is available to download for free by clicking the following link: www.cih.org/media/ox2gxc55/ukhr-autumn-briefing-2024.pdf