13 Mar 2025

CIH response to the Home Affairs Committee's inquiry into asylum accommodation

This submission is made jointly with Kate Wareing, Chief Executive of Soha Housing. Soha Housing is a community-based housing association working in and around Oxfordshire, with about 7,000 homes. Kate Wareing has prepared evidence on alternative ways of delivering asylum accommodation, and this forms the basis of our submission.

Summary

This current asylum accommodation system is expensive, provides poor quality and inappropriate accommodation, and attracts the attention of anti-migrant groups.

The worst and most expensive element of the current system is the use of hotels. This submission argues that hotel accommodation could potentially be replaced by using homes bought on the open market by local authorities and housing associations and managed by them to provide accommodation on the Home Office’s behalf.

This arrangement would be far more cost-effective, and in the longer run provide a pool of property which would be available to local authorities to use for their own temporary accommodation needs, or indeed as long term affordable rental homes.

The Home Affairs Committee is recommended to urge the government to pursue such a scheme on a pilot basis with a view to rolling it out nationally and replacing the current Home Office contracts.

The system of accommodation for asylum seekers in the UK is not working. At the end of September 2024, the initial decision backlog on asylum claims stood at around 100,000 cases. There are around 80,000 new asylum claims being made per year, and there were 34,000 asylum appeals waiting to be determined. As a result, the government has been forced to put large numbers of people in ‘contingency’ accommodation – often hotels – for long periods. As at September 2024, 109,024 people were receiving support (a number which had only fallen slightly on that for the previous year); of these, one-third were in hotels.[1]

There is also a parallel shortage of accommodation for homeless households which has led to increased use of hostels and hotels by local authorities.

From the taxpayer’s perspective, this is cripplingly expensive – the Home Office has been spending around £8 million per day on hotels while councils spend over £1.7 billion annually on all forms of temporary accommodation (TA).[2] From the perspective of those accommodated in hotel rooms, often for over a year, the experience is extremely difficult and often re-traumatising. From the perspective of local residents, businesses and councils in areas with concentrations of hotels accommodating asylum seekers, the impact on communities and tourism industries can be considerable. And of course, asylum hotels make easy targets for anti-immigration protests, exposing residents to extreme hostility.

[1] Based on Home Office statistics, as summarised in House of Lords Library (2025) Asylum accommodation support: Use of hotels.

[2] Costs cited from www.infomigrants.net/en/post/55930/uk-asylum-seeker-accommodation-costs-rocket-despite-government-promises (asylum); and www.bigissue.com/news/housing/councils-spending-homelessness-temporary-accommodation/ (TA).

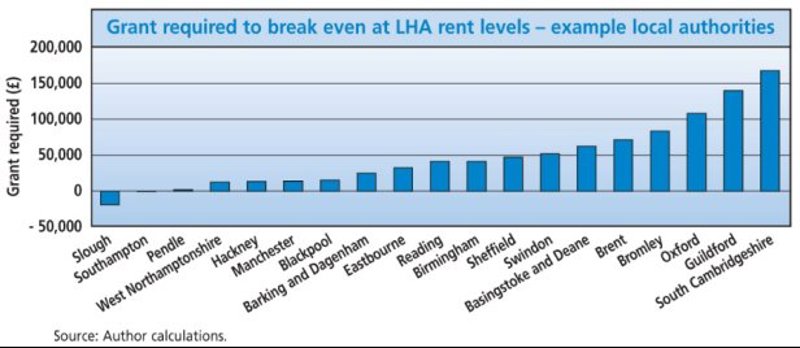

But this could be different. Using available data for every local authority in England we have modelled how much grant would be required to enable a home to be bought on the open market and let at local housing allowance (LHA) levels (see chart – similar calculations would likely apply across the UK).

Compared to current spend on hotel accommodation by the Home Office, the cost of providing the capital grant would be recovered in only seven months from the savings in lower, LHA rent costs compared with hotel charges:

- Average cost per person for hotel accommodation is £54,020 per annum.

- In comparison, accommodating three people in a three-bedroom house saves on average £150,395 per annum (the difference between the cost of a hotel and the rent for a three-bed house at average LHA rates).

- Except for a few outliers with very high or negative costs, the grant required to allow remaining costs (running costs plus interest charges) to be covered by LHA varies from zero to £192,000 with an average of £80,000.

- This means that in 91 per cent of local authority areas in England, the grant needed to enable the purchase of homes to be rented at LHA rents would be fully repaid from revenue savings in under one year.

When we initially made these calculations in summer 2023, 48,000 people seeking asylum were staying in hotels, requiring the procurement of 16,000 homes to replace entirely.[3] Procuring homes takes time – but if we had begun purchasing homes then each home procured would have already repaid the capital grant needed to fund its purchase, and each home procured would now be saving over £150,000 per annum off the current hotel bill. If 2,000 homes had been procured during the last year this would now be reducing costs by £300m this year.

As the determination of asylum claims has quickened, the number of asylum seekers in hotels has fallen to just under 36,000 (September 2024). If 16,000 homes had been purchased in 2023, 12,000 would still be in use in the asylum system (on the assumptions above), leaving 4,000 homes available to meet local homeless families’ needs at a rent equal to the LHA. These could replace dwellings leased at much higher costs by local authorities from private landlords to meet their TA obligations.

Every year that we incur revenue costs on such expensive accommodation is a wasted opportunity to increase the stock of homes available to meet the responsibilities to both asylum seekers and to homeless households. A national supply of TA across all local authority areas would reduce costs to the state, provide better quality accommodation to people through a time of trauma, and add to the supply of affordable rented accommodation.

Even with the new government’s building targets for social housing, the total number of lettings to new tenants is likely to remain below 200,000 per year.[4] By repurposing revenue support, an additional 16,000 new homes could be made available from Home Office hotel spend alone.

Numbers could be increased further if spending on other forms of dispersed accommodation for asylum seekers and TA for homeless households were included too. Payback periods would be longer – but each time revenue spend is used instead as capital grant funding, the nation’s supply of affordable rented accommodation increases.

There are three key prerequisites:

- willingness to make capital outlays before savings are achieved

- willingness on the part of the Home Office and Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government to cooperate to put such a scheme in place

- availability of accommodation at local levels.

The details of this proposal are set out – including costs – in a separate report by Soha,[5] a copy of which can be provided to the Committee on request.

We strongly recommend the committee to consider this alternative and to urge the government to pursue it on a pilot basis. The government has the opportunity to do this with the break clause in the current asylum accommodation contracts in 2026, giving it time to pilot a scheme and potentially roll it out more widely.

[3] Data on asylum support from www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/immigration-system-statistics-data-tables#asylum-and-resettlement

[4] Chartered Institute of Housing Institute of Housing (2024) UK Housing Review 2024, Compendium Table 99.

[5] Available here An-alternative-model-for-funding-asylum-and-temporary-housing.pdf

View parliament's website for more details on the inquiry, or click here to read our response in PDF form.

For more details on our response please email policyandpractice@cih.org.