If there is one thread running through the entire BSHR, it is the need to improve cultures and behaviours across the whole social housing sector.

The BSHR concluded that the imbalance between residents and landlords continues to be one of the largest problems facing the sector, and that this imbalance – underpinned by unfounded assumptions, ignorance, and defensiveness – perpetuates rather than dismantles the stigma and discrimination faced by people living in social housing.

The BSHR also uncovered how poorer repairs and maintenance outcomes were experienced by residents with long-term illnesses and disabilities, and on lower household incomes. Putting this right requires a recognition of past failings and mistakes, but also a renewed commitment to placing the voices of residents more likely to experience poorer service outcomes at the centre of engagement processes.

Through our research, we have developed four principles that social landlords should follow to improve their culture and the inclusivity of their scrutiny activities. The first two of these are tackling stigma and insisting upon empathy, understanding, and professionalism in every interaction you and your operatives have with residents, and making every contact count.

To make your scrutiny activities more inclusive, landlords should also use of range of information to know your silences and inequities and include by design residents who are more likely to experience poorer outcomes from repairs and maintenance services. Doing this doesn’t just improve outcomes for a few groups of residents; rather, actively knowing our silence and practicing inclusion by design results in better service delivery for everyone.

Jump to section:

- Tackle stigma and insist upon empathy, understanding, and professionalism in every interaction you and your operatives have with residents

- Make every contact count

- Use of range of information to know your silences and inequities

- Include by design

- What the statistics tell us about satisfaction with repairs and maintenance services

Tackle stigma and insist upon empathy, understanding, and professionalism in every interaction you and your operatives have with residents

While the need to improve cultures and behaviours is a thread running through the whole of the BSHR, it was noted especially strongly in the findings on repairs and maintenance. The BSHR found that the process of managing repairs and maintenance services can be significantly exacerbated by the inadequate handling of complaints and what was termed the ‘defensive culture’ of too many social landlords. It noted that colleagues in contact centre roles can sometimes push back on what residents are telling them, rather than accepting and acting on their information. It also found that some social landlords were too quick to see complaints as criticism that necessitated a defensive response, rather than an opportunity to make amends and learn lessons.

At the heart of these issues is stigma. Previous research by CIH identified several issues that residents commonly experienced with landlords and their staff. These included making negative assumptions about the lifestyles of residents; contemptuous and discriminatory treatment; actively ignoring their residents; and prioritising business and development over community. For those already more likely to experience societal discrimination, such as residents with long-term illnesses or disabilities and BME residents, these issues were all too often inflected with strands of ableism and racism. Residents told us that language use is key to tackling this appropriately, and actively taking the time to listen to concerns raised by residents and groups of residents that tend to experience poorer service outcomes.

If these issues are not identified and addressed, the engagement you have with residents about your repairs and maintenance services are unlikely to be meaningful, and residents are less likely to trust that any changes will take place afterwards. When stigma pervades the atmosphere of landlord-resident relationships, resident engagement is more likely to be viewed as tokenistic; a tick-box exercise rather than a drive to genuinely learn and improve. Tackling stigma and building a positive, empathetic culture across your whole organisation (and any service providers) is a vital pre-requisite to improving your repairs and maintenance service. Without it, the issues identified in the BSHR will only continue to occur.

Additional resources

Make every contact count

Making every contact count is a principle that originated in health and social care. According to the definition used by the NHS, it is an approach to behaviour change that uses the millions of everyday interactions that we have with individuals to support them to make positive changes to their physical and mental health and wellbeing. It is based on the idea that every interaction we have with someone is an opportunity to help them – to understand their needs and what we can do to better meet those needs. It is opportunistic and strategic at the same time.

In the context of repairs and maintenance, the meaning is slightly different, although the underlying principle remains the same. Social landlords have multiple contact points with their residents through a variety of different activities. Community events, responding to anti-social behaviour reports, and mending a broken tap are all examples of situations where a representative of a landlord will encounter, and have a conversation with, a resident. Residents told us that moving into a new home is also an important contact point that sets the tone for the relationship between the landlord and the occupant. In these scenarios, making every contact count means using these encounters to understand if the diverse needs of residents are being met; if repairs are outstanding or need to be reported; and more widely if residents are happy with the state of repair of their home.

Building on the original NHS definition, the NICE NG6 guidance on the health risks associated with cold homes provide useful guidance that could be adopted by social landlords for this purpose, including recommendations six and ten:

Recommendation six: Non-health and social care workers who visit people at home should assess their heating needs.

Recommendation ten: Train heating engineers, meter installers and those providing building insulation to help vulnerable people at home.

Building on NICE NG6 recommendation six, you should try to ensure that all colleagues who visit people at home are trained to recognise, and have appropriate conversations with residents about, potential repairs issues. Your colleagues should also be empowered to have conversations with residents about how generally happy they are with their home and whether it meets their needs. Beyond this, there are other measures that some landlords are beginning to pioneer, such as equipping their colleagues with a mobile phone app that can be used to photograph potential repair issues and have an initial diagnosis made via artificial intelligence. Equipping frontline colleagues with the training, confidence, and reporting processes that they need to do this can uncover repairs issues that might otherwise go unnoticed, especially if – as the BSHR found – some residents may be less likely to report a problem for fear of discrimination. Residents also told us that the traditional Housing Officer role is a vital yet underappreciated community contact point. They can play an important role in supporting residents when repairs are reported and when they go wrong, but only if they are given the time and space to establish positive, personalised relationships with different communities.

Building on NICE NG6 recommendation ten, you should also enable your repairs operatives – heating engineers, responsive repair teams, and everyone else – to make the contacts they have with your residents count in the same way. Key to this is working in partnership with your contractors, service providers, and/or in-house repairs and maintenance teams to cultivate a culture of awareness and understanding, and helping them to put this into practice inside people’s homes. While fixing the repair at hand is typically the priority, taking a little bit of extra time to scan the walls for other issues and talk to the resident about their needs can pay dividends in identifying and addressing any other issues that may be present. If there are other issues present that the operative can repair there and then, they should be empowered to do so rather than raising an entirely new works request, which can be frustrating for the resident.

Additional resources

Use of range of information to know your silences and inequities

Social landlords collect and hold a large amount of information about their homes, and increasingly about their residents. Using this data smartly and efficiently, and triangulating different data sources with each other, is the best way of obtaining an understanding of your silences and inequities. It can show you who is more likely to be detrimentally affected by poor service provision, and whose voices you are not hearing from in your resident engagement activities.

The sources you can use fall into three groups: qualitative knowledge; internal data collection; and public research and data.

Qualitative knowledge

Qualitative knowledge is the insight and information you receive from the most important people working in your communities: your housing officers, resident liaison officers, and community teams. The BSHR emphasised the need for social landlords to work more closely with their staff and colleagues to improve repairs and maintenance services, and the knowledge and experience of your frontline teams is central to doing this.

As long as you ensure you are doing this appropriately, and following good practice on including colleagues in the improvement of your repairs and maintenance service, you can obtain significant insights into the residents and communities who feel that they are not being listened to, or who are experiencing issues with how repairs and maintenance services are being delivered to their homes.

Internal data collection

Internal data collection is the range of data that you collect on the performance of your repairs and maintenance services, the quality of your homes, and your residents. This includes, but is by no means limited to, asset management data and property information, insights you get from any sensor equipment installed in the homes of your residents, and data from any satisfaction surveys or feedback mechanisms you have in place.

Critically, it also includes information you might hold about your residents, such as their ethnicity, age, support needs, or any language barriers they face. Looking at all this data together, and assessing how it corresponds to the qualitative knowledge you are receiving from your community teams, can help you to see who you need to listen more to.

Improving internal data collection processes is the key aim of the Knowing Our Homes project, established by the NHF to respond to recommendation two of the BSHR. Engaging with this work is the best way of improving how you can know your silences and inequities.

Public research and data

Finally, public research and data is useful for triangulating your conclusions from the two other sources within a national context. For example, we know from the BSHR, the English Housing Survey, the Regulator of Social Housing, and other research that repairs and maintenance service outcomes vary regionally, across different demographic groups, and across different housing types.

At a national level, this data shows that residents with long-term illnesses and disabilities and black and minority ethnic residents consistently experience poorer service outcomes from repairs and maintenance services. If your own internal data and qualitative knowledge says different, it is worth pausing and questioning whether this is accurate, or whether you need to do more work to understand your homes and your residents.

Other data can help too, especially in double checking that you are adequately hearing the voices of residents from different communities who may have specific perspectives you need to incorporate. In areas where you have many homes, the Indices of Multiple Deprivation can help you to understand whether you need to engage more with specific places.

For example, you might find you are having lots of responsive repair requests from places that score highly on crime deprivation. If a significant proportion of these requests relate to windows, doors, gates, or fences, it could indicate that residents are worried about the safety and security of their homes, and that you need to do more work to discern if this is the case.

Keeping a watching brief on public research and data, and repeatedly juxtaposing it with your internal data trends and qualitative knowledge, can help you to spot areas that should be more centrally involved in reviewing how your approach repairs and maintenance.

Taken together, using a range of information sources, and practising triangulation will help you to understand how representative your current engagement and scrutiny processes are of your residents, and if you need to improve that representation. How you can do this is through inclusion by design.

Additional resources

Include by design

Understanding your silences and inequities should directly inform how you design your engagement strategy with residents. You can do this by following best practice in inclusion by design.

In this context, inclusion by design means designing out barriers to resident engagement, and making sure that your methods of resident engagement are inclusive of the needs and requirements of different groups. It is a way of actively engaging with residents who experience consistently poorer outcomes from repairs and maintenance services, and/or who are unable to engage through some of the methods that you might have been using in the past. It is a commitment to working with these residents to understand their experiences and give them a central voice in your decision-making processes. Put differently, practising inclusion by design is an essential prerequisite to designing and delivering repairs and maintenance services that are free of discrimination, racism, and unequal outcomes.

There are at least two ways you can do this. The first is reviewing the composition of any pre-existing groups, scrutiny panels, or forums that inform the design and review of your repairs and maintenance services to understand how representative they are of your residents. Do they adequately include residents more likely to experience poor service outcomes, especially black and minority ethnic residents? Are residents caught up in repairs backlogs sufficiently represented? If you have, for example, a large proportion of your homes in areas of high multiple deprivation, are you ensuring they have a voice? And what about older people, residents in supported accommodation, and leaseholders? Of course, these are questions you should be continually asking of all your resident engagement activities, but they are especially important for reviewing your repairs and maintenance services.

The second step you can take is moving from inclusion by design, to designing to include. More usual forms of engagement and scrutiny, such as residents’ panels, may unwittingly exclude people from participating. Designing to include means delivering bespoke engagement activities that are tailored to the needs and requirements of different groups of residents. Some of the examples of good practice we have heard about in this research are:

- Drawing on community networks and partners to deliver bespoke engagement and outreach sessions, such as through local voluntary sector partnerships. For example, this could entail working with community coffee mornings for older people or local faith groups to gather feedback from residents in safe, supportive environments.

- Undertaking equality impact assessments on resident engagement frameworks to ensure they are inclusive.

- Using British Sign Language interpreters to gather feedback from residents with hearing impairments.

- Holding monthly meetings in-situ in retirement living and supported living services to capture feedback on repairs and maintenance concerns, or appointing a dedicated operative for repairs and maintenance in assisted living schemes, who can act as a single point of contact for residents or their carers.

- Distributing surveys and questionnaires on repairs and maintenance services in multiple formats. This can include printing paper copies so a carer can work through the questions with a resident; ensuring that surveys are offered in plain text format for screen readers; or offering an option to complete over the phone through a translator, in cases where English is not a resident’s first language.

- Building accessibility tools into your website and any other digital communications you send to residents. Residents told us that many social landlords are starting to do this, using tools like Recite Me to make their websites accessible and inclusive for people with different communication requirements. This needs to also include the automatic translation of any downloadable documents (e.g. PDFs) that residents need to access.

- Trialling shorter, snappier forms of engagement, such as drop-in centres or arranging short 5 minutes telephone calls with residents to ask focused questions about their experiences. Residents told us this might be an effective way of engaging with people who lead busy work and family lives, and don’t have the time to commit to a scrutiny panel or other more intensive forms of engagement.

While many of these examples of good practices can be used by different social landlords, designing how you engage with residents should be driven by your assessment of your own silences and inequities. These will inevitably be slightly different depending on who you are, the communities you serve, and how you operate.

Additional resources

What the statistics tell us about satisfaction with repairs and maintenance services

The BSHR found that resident dissatisfaction in the social housing sector was very evident from discussions the panel had with residents.

For many years, however, the exact extent of this dissatisfaction was difficult to quantify. Detailed data on levels of resident satisfaction with repairs and maintenance services was not available, a fact that undoubtedly contributed to sector and government ignorance of the severity of damp and mould issues.

According to the English Housing Survey (EHS), the prevalence of damp in English housing has hovered at around four per cent for over a decade, following a substantial decrease from 1996. In July 2023, the EHS included a new module on ‘Satisfaction and Complaints’ that quantified resident dissatisfaction with repairs and maintenance services in social housing.

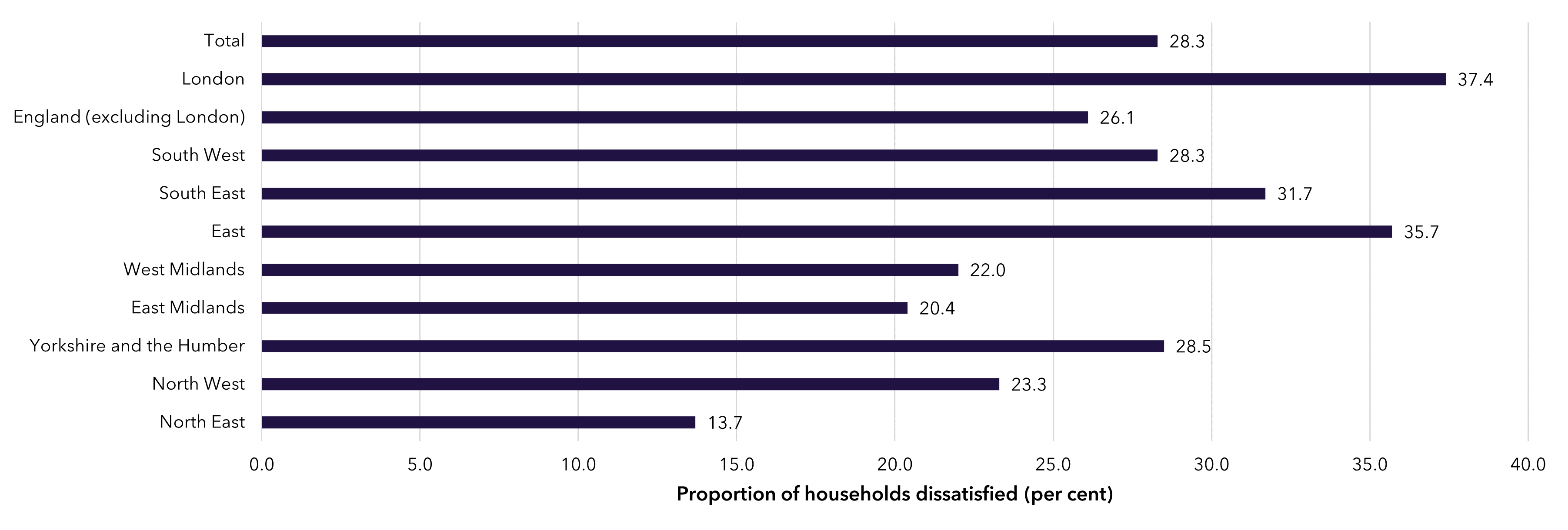

The data showed that 28 per cent of social rented households – over 1.1 million in total – were dissatisfied with the repairs and maintenance services provided by their landlord. Satisfaction levels also varied quite considerably across England, ranging from 52 per cent in London to 82 per cent in the North East of England.

Residents with a long-term illness or disability were also more likely to be dissatisfied with the repairs and maintenance services provided by their landlord, and outcomes also varied by ethnicity, with Asian households far more likely to be dissatisfied than other groups.

The EHS also collected data on the main reasons for household dissatisfaction. In the social housing sector, the main reasons given were that the ‘landlord does not bother’ and that the ‘landlord is slow to get things done’. A not insignificant proportion of social rented households also said they were dissatisfied because the work done was of a poor quality, or that their landlord only does the bare minimum.

This data will be deepened significantly when the first results of Tenant Satisfaction Measures (TSMs) are published in 2024. This will tell us resident satisfaction with repairs, as well as satisfaction with the time taken to complete their most recent repair and how well maintained their home is. Going forwards, tracking changes in the TSMs over time is the main way we will be able to understand if repairs and maintenance services are improving.

Until then, the EHS data is a necessary reminder of the importance of working with our residents to understand what has gone wrong in the past, and how it can be put right in the future.